Tom Koontz Jr. has been a truck driver all of his life. He has hauled on the dangerous ice roads of Alaska, and driven in the legendary road trains of Australia’s outback. Then in October 2016, while making a cross-country run here in the U.S., Koontz woke up with a vocabulary of seven words. Two of those words were profane; fitting, given his anger upon learning he had suffered an atypical stroke at age 55. After 35 years driving semis, his career was over and his livelihood gone.

Koontz’ best friend, Duva Garlow, had been his co-driver for a year and a half when Koontz had his stroke near Atlanta, Georgia. “I knew something was wrong when he said, ‘Me go doctor,’” Garlow recalled. “And he hates doctors. So I knew something was major wrong.”

Koontz’ limited vocabulary and his intense frustration at not being able to communicate caused a ruckus at the hospital. “Let’s put it this way,” Garlow explained. “Those few words were the total extent of his vocabulary. And he was frustrated and he raised his voice, so security thought he was being abusive. I had to ask them to step down. I had to tell them, ‘He’s not abusive. Something is wrong.’”

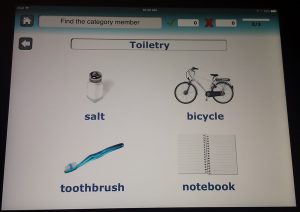

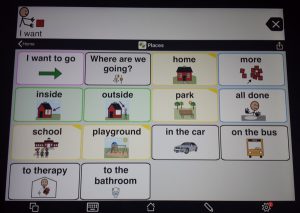

Koontz began the hard work of recovery at Missoula’s St. Patrick Hospital. Diagnosed with expressive aphasia, he began working with speech pathologist Kerrigan O’Connell at the hospital’s Wellness Center. O’Connell sent Koontz to MonTECH to borrow an iPad loaded with the communication app Proloquo2go, as well as an app designed specifically for aphasia. Koontz began using the iPad to communicate, and to practice his therapy. He has made great progress. Garlow is proud of how tenacious Koontz is: “He’s never quit trying,” she said. Koontz added, “I won’t quit. I refuse. I’m getting better every day.” That statement alone reflects the tremendous gains he has made.

Prior to his stroke, the two best friends had purchased 160 acres of remote wild land. They planned to build a cabin for each of them, then share and work the property together. Their land is nine miles from the nearest paved road, but the idea of living off the grid and as self-sufficiently as possible appeals to both Koontz and Garlow.

Now that Koontz is no longer able to drive, they have adjusted their plans accordingly. Koontz is applying for a grant for his own iPad and mobile hot spot. If the grant is approved, he will use the iPad for more than communicating and participating in his continued therapy. Garlow and Koontz plan to start a new business selling honey and eggs, and Koontz can use the iPad to keep track of orders, set reminders, keep lists, and track inventory. Assistive technology will be a critical component of his future success.

“Different people, family members, wanted us to sell the land,” Garlow said. “Too remote. But the first time Tom expressed a true emotion after the stroke, we had gone up to the land, and he got out of the truck and he said, ‘Peace.’” Garlow smiled at Koontz. “The stroke is delaying our dream. It’s not cancelling it.”